(Note: To my great surprise, director Chris Windsor contacted me shortly after this was published, answering the question posed in the final line of the article. He also provided his own account of the making of Big Meat Eater, which you can read at Straight.com.)

“It’s not easy to explain precisely why this is one of the best movies of the year.” So wrote Brit critic Kim Newman about the film Big Meat Eater, in the April 27, 1984, issue of the London listings mag City Limits. He was hardly alone in his corkscrew praise. The unlikely release in the U.K. of Big Meat Eater—a micro-micro-budgeted sci-fi horror musical shot in White Rock and Steveston by a couple of former SFU students—was met with an even unlikelier round of acclaim when it crossed the Atlantic, where Canadian films generally went to die. The film drew universal raves from the snobs at Time Out, the NME, and the Times. And it wasn’t just the critics who were impressed.

“I heard from Vicki Gabareau,” recalls the film’s producer Laurence Keane, calling the Georgia Straight from his home in Kitsilano. “She was actually in England at the time, and she said there was a line-up around the block at the theatre. Even to me, it’s still a surprise.” Two years earlier, the now defunct Vancouver East Cinema on Commercial Drive enjoyed the same phenomenon when Keane and his partner, director Chris Windsor, first opened their film to a hometown audience. What viewers beheld was a cockamamie mash-up of suburban kitsch, '50s sci-fi, and voluptuous comedy-horror, with intermittent musical numbers that swung from big band jazz to Devo-esque new wave—plus at least one little shout-out to Vancouver’s U-J3RK5.

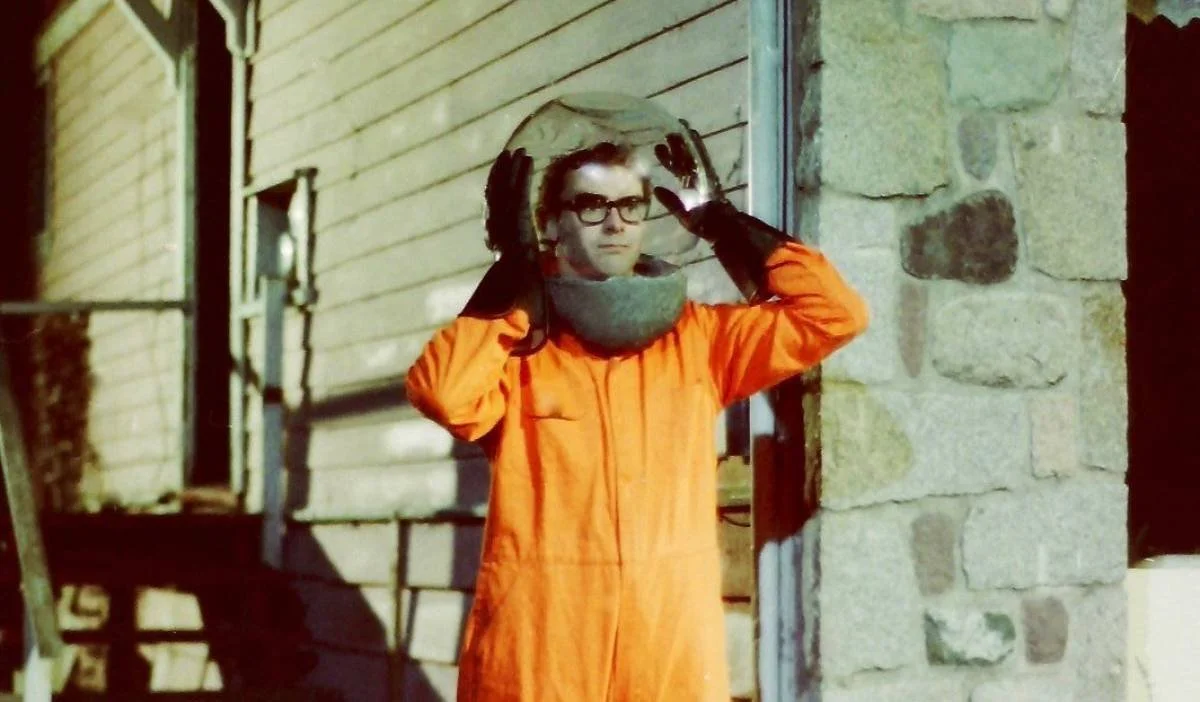

“I’ve always thought by making something really, really provincial, you really make something universal,” says Keane, explaining that he and Windsor wanted to lampoon “the earnestness of Canadian TV and film” and its high-minded (read: boring) approach to multiculturalism, all while satisfying Keane’s more mercurial jones for '30s musicals and tacky '50s drive-in fare. And so, in no coherent order, Big Meat Eater introduced audiences to the relentlessly cheerful and even more relentlessly nerdy butcher Bob Sanderson (George Dawson, The Grey Fox), his murderous 350-pound assistant, Abdulla the Turk (Edmonton blues singer Big Miller), and a cast of characters that otherwise included a family of superstitious Moldavians and their genius son, Jan Wczinski (played by Orphan Black’s Andrew Gillies, inexplicably, with a British accent), plus a corrupt Mayor flanked by two violent thugs (one of them is called Alderman Sonny the Weasel), and a couple of robot aliens bent on extracting Burquitlam’s most-precious resource, Balonium.

Their plan? In the words of Kim Newman, it’s not easy to explain, but after being killed by Abdulla and stored inside Bob’s meat locker, the Mayor is revived Plan 9-style and then dispatched to rubber-stamp the construction of “the Vision of Tomorrowland”. Uncannily foreshadowing Expo, this is actually a base for the Balonium-hungry extraterrestrials. Unhinged plot notwithstanding, what audiences and critics dug about Big Meat Eater, as it made its way East—a cover story in Toronto’s NOW Magazine would follow in 1983, along with a rave in Variety—was its aggressively proud and cheerful shittiness.

“The great thing about White Rock at the time is that it was pretty economically depressed,” explains Keane, with a chuckle. “There were a lot of second hand stores, so any time we needed any props, we’d just send somebody out to pick up what we needed.” Presumably this included the wind-up toy robots and tin flying saucer that famously took the place of any real special effects. Industrial Light and Magic this wasn’t. What it was, in further pursuit of Keane and Windsor’s goals, was a self-aware kiss-off to a national film industry that treated Vancouver like a bunch of Moldavian immigrants.

“There was a lot of prejudice against us from the East Coast,” says Keane, who would later organize a “dada-esque” film collective called WIMPPS, or the Western Independent Motion Picture Producers Society, with colleagues including Sandy Wilson and Jack Darcus. “We were considered the hicks from the sticks, which I found very interesting since I was born in London, England, I grew up in Toronto, and I went to school in L.A. But no, we’re the unsophisticated types out here in Vancouver.”

It was that precise attitude that prompted Keane and Windsor to revive a project they first toyed around with as SFU students in the mid-'70s. After returning from a stint at the USC film school, Keane banged out a version of what would become Big Meat Eater at his parents’ house in White Rock in early 1980. Gradually, Phil Savath was drafted to “punch-up” the script, on the advice of composer J. Douglas Dodd, whose jazzy soundtrack for 1977’s Skip Tracer caught the ears of Keane and Windsor. Dodd also brought along a handful of ready-made songs, including the title number, which was incorporated into an unforgettable scene in which Abdulla enthusiastically massages and flings around some ground beef, prior to a failed attempt to kill Bob with a string of sausages. (“They sold that meat,” Keane assures. “That meat was not thrown out.”)

Another of Dodd’s off-the-shelf numbers, the insanely catchy “Heat Seeking Missile”, provided the film with its climactic number, and featured lyrics and vocals by the Skip Tracer himself, David Petersen—who had worked, like Savath, on David Cronenberg’s Edmonton-made film, Fast Company. Other numbers were hashed out on napkins at “a Chinese restaurant on 2nd and Burrard”, yielding the deadpan synth epic “Mondo Chemico” and the phenomenally accomplished swing number, “Who’s That Man?”, which accompanies butcher Bob on his stroll through Burquitlam in the film’s opening scene. (“He’s a butcher, what a zero, yeah the butcher, not a hero, he’s the butcher, butcher, butcher, butcher, BOB!”)

Keane had roughly half the 150K budget in place when principal photography began in December 1980. Eschewing any government money, which wasn’t available to them anyway, Keane and Windsor sold $5,000 “units” through their BCD Entertainment Corporation. Keane would go meet investors “and then I’d come back to the set, having sold another unit.” An unusually warm winter made for a largely untroubled production, although it wasn’t entirely pain free. Keane recalls stumbling into a room full of weeping musicians during a visit to the recording studio. “I’m in high spirits when I walk in, and I say, ‘What’s going on guys?’” he remembers. “And they tell me that John Lennon’s been killed.”

It would be another two years before the finished film saw the light of a projector, in advance of its long strange trip to international cult status. Britain ate it up thanks largely to the efforts of painfully hip distributor Palace Pictures, whose catalogue included the films of Werner Herzog and Ed Wood, plus titles like The Evil Dead, and who festooned the VHS release of Big Meat Eater with a flexidisc and artwork by Cramps album illustrator Graham Humphreys. The film foundered in the States, however, fumbled by New Line Pictures, which had scored big with the not entirely unrelated work of John Waters. Even worse, New Line actually lost the 35mm internegative—leaving Keane to seriously contemplate what he was told when he met with the company in New York. “The guy said, “You just signed a deal with devil’," Keane recalls. “Oh, great.”

Now here’s the good news: when Big Meat Eater returns to the big screen on Monday (January 29), thanks to the Cinematheque’s vital series of B.C.-made films, The Image Before Us, patrons will be treated to a crystal-clean 2K high-def DCP restoration of the film, reconstructed from an original 16mm print, amazingly, to match the same 35mm print that New Line managed to lose. If Big Meat Eater was conceived as something of a “fuck you” to federal cash, we should now give humble thanks to Library and Archives Canada for undertaking such a monumentally daft project.

But it’s also a vital project, culturally speaking. We can very reasonably declare that Big Meat Eater cracked the nut on a specific kind of transcendentally kitschy Canadian humour, looking forward to John Paiz’s wonderful Crimewave (1985) and the work of Guy Maddin, who "liked Big Meat Eater a lot,” according to Keane. “There might have been a slight influence there, I don’t know. But I’ll take credit for it.” Meanwhile, you could easily picture Bob Sanderson as the sixth member of SCTV’s 5 Neat Guys, who made their debut after Big Meat Eater was in the can.

It’s a fitting and well-deserved victory lap for a shaggy dog story out of White Rock. The only thing lacking is director Windsor, who’s been MIA, apparently, for decades. “Last thing I heard, about 15 years ago, is that he was living in Thailand,” reveals Keane. “He had a lot of talent. It’s a shame. He was a very, very good director.” Rather poignantly, Windsor seemed to predict his own future in a 1984 interview with U.K. critic Phillip Bergson, lamenting that, with Canada’s eternally fitful film industry: “I just wonder whether I’ll make another film myself.”

Us too.

Chris Windsor—where are you?

Georgia Straight, January 2018